Toast, Caramel, Toffey and Sweetness. A look at the sugars and sugar compounds in Beer.

Beer! It’s pretty sweet stuff. It’s also, by nature, sweet stuff: Beer is generally made from wort that is extracted from mashed grains, a mixture containing many sugar compounds, and modified sugar-sugar compounds,and sugar-protein compounds. In this article we will explore the constituent sugar compounds in beer, where they come from and how they impart certain flavors in beer.

The Major Players.

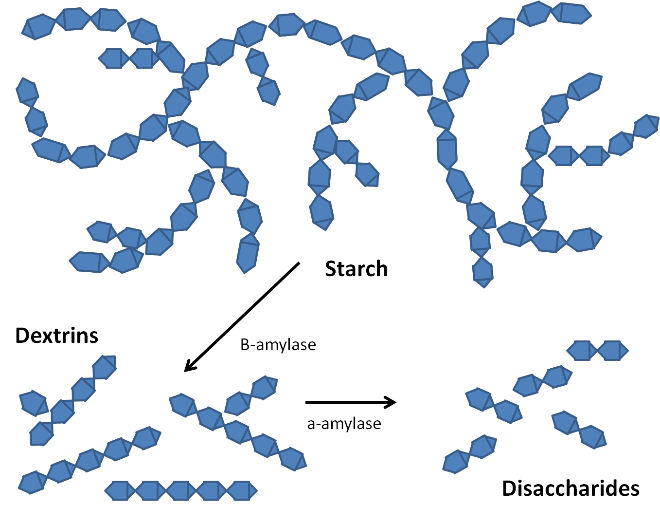

Sugar is a six carbon compound that exists in two forms, strait chain and ring structure. Both of these features give sugar unique chemical properties.For most of our discussion we will be dealing with sugar in solution, such as sugars in wort, which causes the sugar to form a cyclic structure (Fig 1.)

Figure 1. Shapes of Sugar: The above figure shows the structural forms of

Sugar. As you can see the transition from linear form to cyclic causes the

deprotination (loss of H+) to the environment.

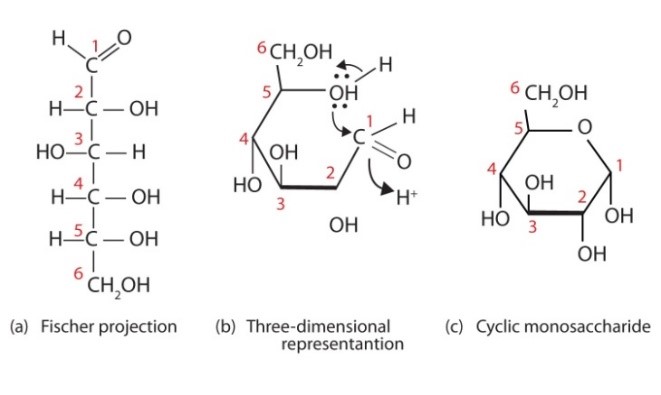

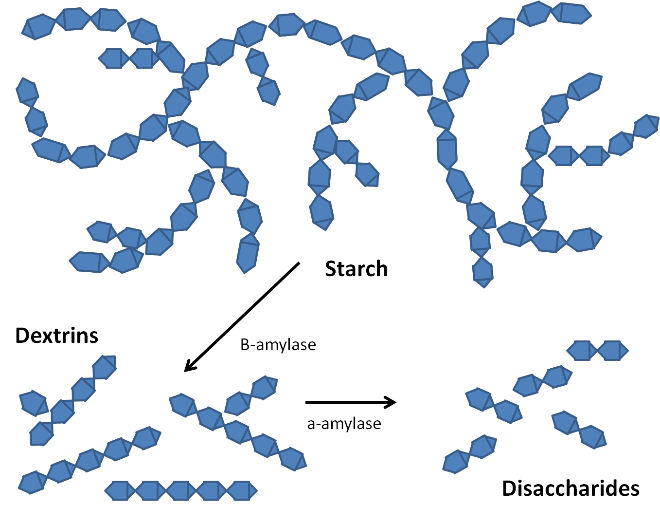

In a cyclic form sugar can form many linkages and form small chains (like maltotriose), long chains (polysaccharides) or multiple branching chains(starch). In the malt itself the sugars are stored as starch, a heavily branched polysaccharide, that optimizes sugar storage within the plant tissues and cells. Mashing is the process by which we convert the starches to fermentable and non-fermentable sugars through the activation of amylases (more on this class of enzyme can be found elsewhere). After mashing out (lauter)your wort will have a mixture of sugars in its solution. The amount of sugars in your solution by percent is called Brix, and by density: specific gravity.Research shows that across multiple mashes and variant temperatures the general breakdown of malt derived sugar looks like this (Table 1.)

| Fructose | 2.6% | Monosaccharide |

| Glucose | 21.5% | Monosaccharide |

| Sucrose | 4.5% | Disaccharide |

| Maltose | 46.6% | Disaccharide |

| Maltotriose | 20.6% | Trisaccharide |

| Maltotetraose | 4.5 | Tetrasaccharide |

Table 1. Abundance of Malt Derived Sugars: Compiled GC data

from 15 different 2 row malt mashes and averaged. Taken from Otter 1967 (1)

In table 1 the sugars are grouped by increasing chain length, and abundance in wort. Its worth noting that Monosaccharides and Disaccharides (one and two chain sugars respectively) are fermented by ale yeast, while Mono-, Di- and Trisaccharides are fermented by Lager yeast, owing to its drier mouthfeel. Maltotetraose and larger chain sugars are referred to as Dextrins (figure 2), a class of long chain sugars that impart sweetness and mouthfeel to wort at higher mash temperatures 156-162. Great for chewy beers and most brew yeasts do not chew them up. The exception here is bacteria and Brett which have their own internal amylases that will chew up these sugars. Woe to the brewer that makes a Bretted Scottish Ale for it will be dry, dry, dry, dry for the lack of residual sugar… and likely rubbery… because Brett. So, for sweetness high mash temp leaves residual sugars that won’t ferment out. While a lower mash will generate small chain sugars that are easily fermentable, creating a drier beer.

The story doesn’t end herewith sugars either. Traditional sours and farmhouse beers were generated with turbid mash, called so for its white and opaque color, a mash with high concentrations of starch. To achieve this a turbid mash is partially lautered before the temperature is stepped up to 148-160F for amylase rest. This leaves lots of starch for bacteria and Brett as these beers age for months without being stressed, which leads to a less robust beer. The sugars we get out of a mash have very big implications for out beer downstream, especially with regard to the microbes doing the work.

Figure 2.Representation of Sugar molecules found in beer.

So far we have covered lots of the simple sugar and sugar chains, but there is more to this sweet story. Our wort is not just made of 2 row (unless it is..??), it is made of modified malts and specialty malts. Many of these malts go through special kilning, roasting,smoking, firing process that modify the sugars further to form unique compounds that lead to unique sugar complexes or interactions with proteins to form flavors that add depth and complexity to our beers.

Caramelization

Many beers and malts carry distinctive sweet notes that have a beyond sweet richness, and lingering syrup like notes. These classes of highly modified sugars are called Caramels and come in three distinct forms: Caramelans, which are 24 carbon sugars; Caramelens which are 36 Carbon sugars; and Caramelins which are 125 carbon sugars. These chains are made from the reaction of small sugars with heat and oxygen to form larger chains. As these compounds are heated together, they release diacetyl which gives off buttery notes that are a hallmark of caramel. Crystal malts are very high in caramels because they are wetted before roasting. This wetting releases starches and increases their active sugar content when the crystals are kilned giving these malts a higher caramel content. Other malts that have high caramelization are the Cara malts of Germany and roasted malts of England. These compounds are also unfermentable and leave distinct flavor and aromas.

Melanoidins

Toasty, bread crust,roasted marshmallow, rich toffee flavor-these the the Melanoidens. A unique group of sugars that through heat combine with amino acids (small bits of protein) to form long polymer chains with a lot of flavor. Like caramelization this process is known as sugar browning reaction from the distinct color changes these chemical changes have on the sugars. Produced primarily in low water environments such as baking or roasting these compounds can be found on many kinds of German malts such as Vienna, Munich, cara-Munich, aromatic malt, chocolate malts, and of course Melanoidin malt. These malts go through a kilning process where they are repeatedly heated and cooled, to produce melanoidins in a dry atmosphere,unlike caramels which are produced by wetting the malt. The heating and cooling also prevent the formation of caramels which happen at higher temps. The process was originally described by French Chemist Louis-Camille Maillard (pronounced My-ard) in 1912 while trying to replicate protein synthesis. Beyond sweet the Melanoidins give a umami taste that gives a bready, hardy, fullness flavor to beer. Melanoidin malt is often used to substitute biscuit malt. A great tool to have in your arsenal for the production of classic rich German styles. Another way to naturally generate these compounds is through decoction. The heating of wort and grain in the kettle produces these compounds,especially in protein rich wort. Also noteworthy is these compounds do not ferment leaving the brewery with the sweet toasty crumb flavors that are so pronounced in Bocks and Oktoberfests.

Conclusion

Many factors come together to produce a great beer. Water, Malt, Hops and Yeast all play their part. Yeast is often recognized as one of the major contributors to beer flavor, although we must give malt, and more importantly, sugars their time in the sun. I’m always amazed at how many unique beers a brewery can make using their in-house strain. This diversity comes from the balance of mashing temp and malt choice. So many options are available to the artful brewer who can balance mouthfeel and flavor or Sweetness and dryness. So, go forth home brewer with your new appreciation of the contents of your wort. Make artful brewing science in action!

References

- G. E.Otter, L. Taylor: DETERMINATION OF THE SUGAR COMPOSITION OF WORT AND BEER BY GAS LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY,November‐December 1967 Journal of the Institute of Brewing